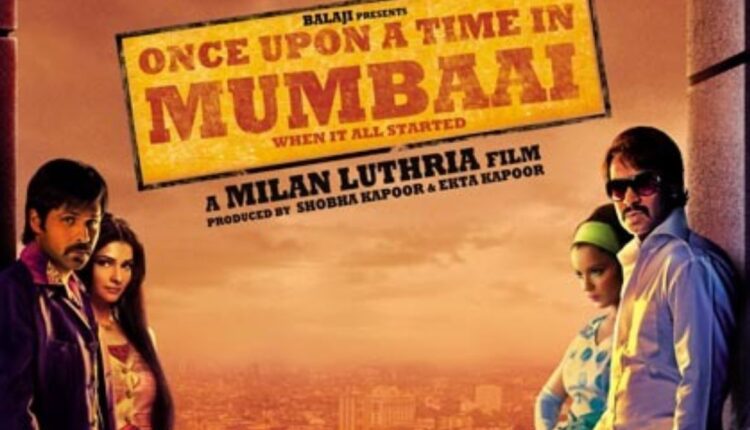

Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai takes us back to the beginnings of gangsterism in Mumbai. Milan Luthria excels in creating smouldering combustive stress between two mean, menacing men… Remember Devgn and Saif Ali Khan in Luthria’s Kachche Dhaage, and on a more satirical note, John Abraham and Nana Patekar in Taxi No 9211.

In Once Upon A Time…. the conflict between Devgan (who is NOT Haji Mastan) and Emraan Hashmi (who is NOT Dawood) is placed in a far more complex and challenging scenario. The screenplay (Rajat Arora) takes into view the entire gamut of grime in the canvas of crime that cannot be hidden by the surface glamour and glitter.

The vintage cars, the costumes, and that attitude of rebellious abandon come through in the inner and outer styling of the characters. The people in Luthria’s panoramic view of Mumbai in the late 1960s and 70s are steeped in a cinematic realism. Neither a part of that period nor a completely true representation of an era gone-bye-bye, the characters hover in a no-man’s-land populated by fascinating details of the past recreated with a tongue-in-cheek broadness of purpose.

There are bouts of suppressed satire in the way the whole era of the genesis of the underworld is represented. For example, Emraan Hashmi befriends and sleeps with a woman who looks a lot like a Bollywood actress whom Raj Kapoor had introduced in a film, and Dawood had befriended and allegedly impregnated.

Often, the characters are an amalgamation of furious folklore and long-forgotten newspaper headlines of the 1970s. Kangana Ranaut plays an actress from the 1970s who gets the hots for the Robin Hood-styled smuggler-hero. Later, she is discovered to have a congenital heart disease (a la Madhubala, who came two decades before the events of this film are supposed to unfold). But look at the irony! It’s her smuggler-hero lover who dies of a wounded heart.

Maybe we shouldn’t give away the plot. Because the plot never gives itself away. It never betrays a phoney intent of purpose. The narrative unfolds through the first-person narration of a troubled, wounded cop, played with remarkably restrained bravado by Randeep Hooda. Indeed, this is the most accomplished performance in the film. He’s partly a gallant law enforcer and partly a victim of a system that breeds inequality, corruption and finally, self-destruction.

Hooda is wry, cynical, bitter, anguished and yet able to see the humour of a situation that one can ride only by sublimating its gravity. As for Ajay Devgn, he continues to evolve with every performance. As a gangster from the 1970s, Devgn brings to the table a clenched self-mocking immorality. He stands outside the character even while internalising the performance.

Director Milan Luthria imparts a keen eye for detail to the storytelling. Some bits in the second half get shaky, such as the predictable club songs and the repeated use of overlapping editing patterns to convey the rising tension between the mentor and the protégé turned tormenter. But the director’s command over the language of outlawry is unquestionable.

Emran Hashmi as Devgn’s uncontrollable protégée gets the look and body language right. His courtship of Prachi Desai to the accompaniment of romantic hits from the 1970s (e.g Raj Kapoor’s “Bobby”) is engaging. Understandably, the two ladies are reduced to pursing their lips and wringing their hands as the story progresses. The film’s best, most charming and heartwarming moments come in the early stages of the drama between Devgn and Ranaut. Their growing fondness for one another is recorded in scenes and words written by a poet who can see the humour behind mutual attractions.

The real hero of this film is the writing. Rajat Arora’s dialogues flow from the storytelling in a smooth flow of poetry and street wisdom. Aseem Mishra’s sharply-evocative cinematography gives to this rugged and razor-sharp look at Mumbai’s mythic mating with crime an urgency that simply can’t be ignored.