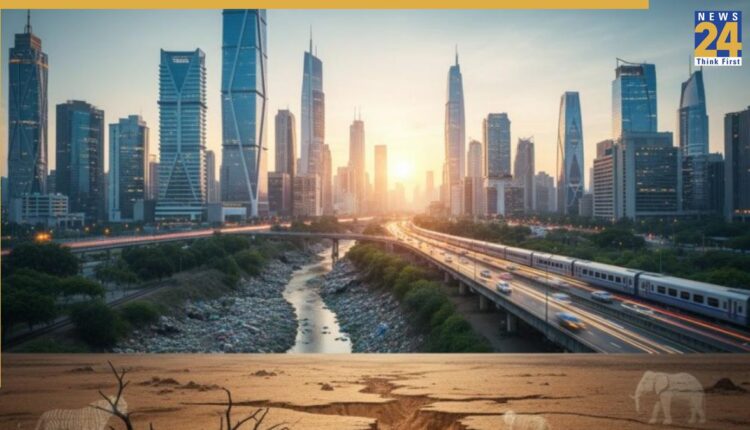

India stands at a defining ecological moment. Beneath the optimism of record growth, a silent erosion is reshaping the nation’s soil, forests, and species. Scientific assessments released in late 2025 paint a stark picture of vanishing land fertility, shrinking biodiversity, and an accelerating climate crisis that could redefine how the country feeds itself and sustains its natural heritage.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s State of Food and Agriculture 2025 report, India ranks among the nations facing the sharpest agricultural yield losses due to human-induced land degradation. Nearly 1.7 billion people globally live in areas of declining crop productivity: over one-third of them in South and East Asia. Within India, the situation is particularly dire: the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) estimates the country loses 5.3 billion tonnes of soil every year through erosion and poor land management. That translates to the loss of nutrients, directly impacting agricultural output and food prices.

The Vanishing Land Beneath Our Feet

Satellite-based data from the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) reveal that 97.85 million hectares, or nearly 29.77 % of India’s landmass, now shows signs of degradation. The most affected zones include Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Jharkhand, and the Himalayan foothills, where soil erosion, desertification, and mining-related land disruption are expanding fastest.

Across central India, the consequences of deforestation and erratic rainfall are clear: altered land surfaces, reduced groundwater recharge, and accelerated siltation in rivers. This translates directly into floods that come sooner, droughts that last longer, and farmlands that produce less each year.

The economic toll is significant. A key 2018 report from TERI, often cited by NITI Aayog, warned that degraded land was already costing India about 2.5% of its GDP annually through reduced crop yields, water scarcity, and disaster recovery expenses.

In short, India’s land isn’t just eroding – it’s bleeding economic and ecological value.

Biodiversity Under Pressure

Parallel to its land crisis, India’s biodiversity is under extraordinary strain. In October 2025, the government launched the National Red List Assessment, the most ambitious wildlife audit in the country’s history. Led by the Botanical Survey of India and the Zoological Survey of India, the five-year initiative will evaluate the extinction risk for approximately 11,000 species, including 7,000 plants and 4,000 animals.

Environment Minister Kirti Vardhan Singh, unveiling the plan at the World Conservation Congress in Abu Dhabi, called it a “turning point in how India values its living wealth.” The goal is to create a nationally coordinated database by 2030 that tracks the conservation status of every major species, aligning India’s efforts with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

During Wildlife Week 2025, five new conservation projects were also launched, targeting species such as river dolphins, sloth bears, gharials, and tigers outside traditional protected zones. These projects acknowledge a changing reality: conservation can no longer rely only on fenced parks. With human-wildlife encounters increasing due to shrinking habitats and climate disruptions, the new focus is on coexistence rather than conflict.

Climate Change as the Great Multiplier

Land degradation and biodiversity loss are now converging with climate change to form a triple emergency. The Himalayan region, long regarded as India’s ecological crown, is melting faster than ever. This has significantly increased the threat of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) – a hazard that was rare before 1950 but now poses a growing risk to downstream communities.

In August 2025, one such flood in Uttarakhand killed many people and left dozens missing when a retreating glacier burst, inundating a valley that once fed local farms.

These cascading events show that land, climate, and biodiversity cannot be separated. Each loss amplifies the others: deforestation worsens floods, floods destroy soil, soil loss kills plant diversity, and reduced vegetation further disturbs the climate. The country’s National Adaptation Plan, expected to be unveiled at the UN COP30 climate conference in Brazil, is designed to break this feedback loop by prioritizing ecosystem-based adaptation, restoration of degraded land, and community-driven conservation.

Lessons from the Ground

In the arid districts of Rajasthan’s Barmer and Gujarat’s Kutch, farmers are already living the crisis. Crops that once thrived on monsoon moisture now fail under erratic rainfall and degraded soil. Many have turned to agro-forestry, reviving native species like Prosopis cineraria (khejri) and Ziziphus mauritiana (ber) that hold the soil and provide both fodder and fruit. These local solutions demonstrate that sustainable land management is not just an environmental issue – it’s a livelihood strategy.

In the Western Ghats, one of the world’s eight biodiversity hotspots, conservationists have begun blending traditional tribal knowledge with digital monitoring. Using drones and camera traps, local communities now help map elephant and leopard corridors, creating early-warning systems that reduce both crop damage and animal fatalities.

Such bottom-up initiatives embody what India’s ecological future could look like: adaptive, inclusive, and driven by the people most affected.

The Economics of Ecology

The financial markets are beginning to price these ecological risks. Analysts point to sectors like renewable energy, water management, green construction, and sustainable agriculture as long-term beneficiaries of India’s adaptation drive.

Companies involved in key areas are drawing investor interest, including soil conditioners, micro-irrigation, and wastewater treatment.

Environmental equities are slowly evolving from niche to necessity. The logic is clear: economies that fail to conserve their natural capital risk losing their financial one.

The Way Forward

India’s environmental crisis is no longer invisible, it’s measurable, mappable, and, increasingly, monetized. What remains uncertain is whether political will can match scientific urgency. The upcoming National Adaptation Plan and biodiversity roadmap must be backed by consistent funding, transparent monitoring, and citizen participation.

But beyond policy, the real shift must happen in perspective. Soil is not just an agricultural input; it is the foundation of civilization. Biodiversity is not a luxury of forests; it is the invisible machinery that keeps air breathable, water clean, and crops pollinated. When these systems collapse, so does the economy that depends on them.

India’s ecological balance sheet is in deficit, but the country still holds a rare asset: a young population, rich traditional knowledge, and a fast-growing green economy. Whether it becomes a model for sustainable growth or a cautionary tale for the world will depend on how quickly it acts to heal the land that sustains it.